How to brief a brand agency (without wasting everyone’s time)

Updated on

December 27, 2025

Reading time

7 minute read

How to brief a brand agency (without wasting everyone’s time)

⚡ Quick Answer

To write an effective brand brief that saves time and improves agency results, clearly define your company's context, the specific challenge, and what success looks like. Provide relevant constraints and background info, but avoid being overly prescriptive. Focus on outcomes, not exact solutions, and ensure all stakeholders are aligned before briefing. This clarity enables agencies to create strategic work rather than guess or execute blindly.

Bad briefs lead to bad work. This isn’t controversial—everyone in the industry knows it. Yet most clients have never written a brand brief before. They’re experts in their own business, not in commissioning creative work. The result is briefs that are too vague, too prescriptive, or focused on the wrong things.

A good brief doesn’t constrain creativity. It focuses it. The best work comes from clients who know what they need—even if they don’t yet know what they want.

What actually belongs in a brief

A useful brand brief answers the questions an agency needs to do good work. Not the questions you think sound impressive, or the details that feel important internally, but the specific information that shapes creative direction.

Start with context. What does your company do? Who do you serve? What’s your current market position? How do customers describe you today? An agency needs to understand where you’re starting from before they can help you get somewhere new.

Articulate the challenge. Why are you doing this project now? What’s not working about your current brand? What business problem are you trying to solve? The clearer you are about the problem, the more likely you’ll get solutions that address it.

Define success. What does a good outcome look like? This isn’t about deliverables—it’s about impact. A successful project might mean clearer differentiation, better recruiting, higher close rates, or smoother expansion into new markets. Name the actual goal.

Identify constraints. What’s fixed and what’s open? Is the name changing or staying? Are there brand elements that must be retained? What’s the budget range? What’s the timeline? Constraints aren’t obstacles to creativity—they’re parameters that make creativity useful.

Share relevant inputs. Customer research, competitive analysis, internal strategy documents, previous brand work, stakeholder opinions—anything that helps the agency understand your situation. More context is almost always better than less.

The questions you should be able to answer

Before you write the brief, pressure-test your own clarity. If you can’t answer these questions, you’re not ready to brief an agency—you’re ready to do internal alignment work first.

Who do you serve? Not a vague demographic, but a specific description of your ideal customer. What do they care about? What problem are you solving for them? Why do they choose you over alternatives?

What are you really selling? Not features—value. What does the customer get that they couldn’t get elsewhere? What transformation do you enable?

Who are you competing with? Direct competitors, yes, but also indirect alternatives and the option of doing nothing. How are you positioned relative to each?

What makes you different? This is the hardest question and the most important. If you can’t articulate genuine differentiation, the agency can’t create it for you—they can only express what’s actually there.

What do you want people to think and feel? When someone encounters your brand, what impression should they form? What emotions do you want to evoke?

Red flags in your own brief

Some brief language signals confusion that will undermine the project.

“We want to appeal to everyone” is a positioning problem. Brands that appeal to everyone differentiate from no one. If you can’t identify who you’re specifically for, you’ll get work that’s generically pleasant but strategically empty.

“We’ll know it when we see it” abdicates responsibility. Agencies aren’t mind readers. If you can’t articulate what you’re looking for, you’re setting up an expensive guessing game. It’s okay to not know exactly what you want, but you should know what problem you’re solving and what success looks like.

“We just need a logo” underestimates the work. A logo is an output of strategic thinking, not a starting point. If you’re asking for a logo without engaging on strategy, you’re asking for decoration rather than brand building.

“Make it pop” or “make it modern” aren’t directions—they’re vibes. Every agency interprets these words differently. If you’re using subjective adjectives without examples or specificity, you’re not communicating clearly.

“Our CEO wants something like Apple” reveals a stakeholder alignment problem. Referencing a massive consumer brand for a b2b startup isn’t useful—the contexts are too different. And if the CEO’s personal taste is driving brand decisions, the agency needs to know that early.

How much direction is too much

There’s a balance between providing helpful constraints and micromanaging creative work.

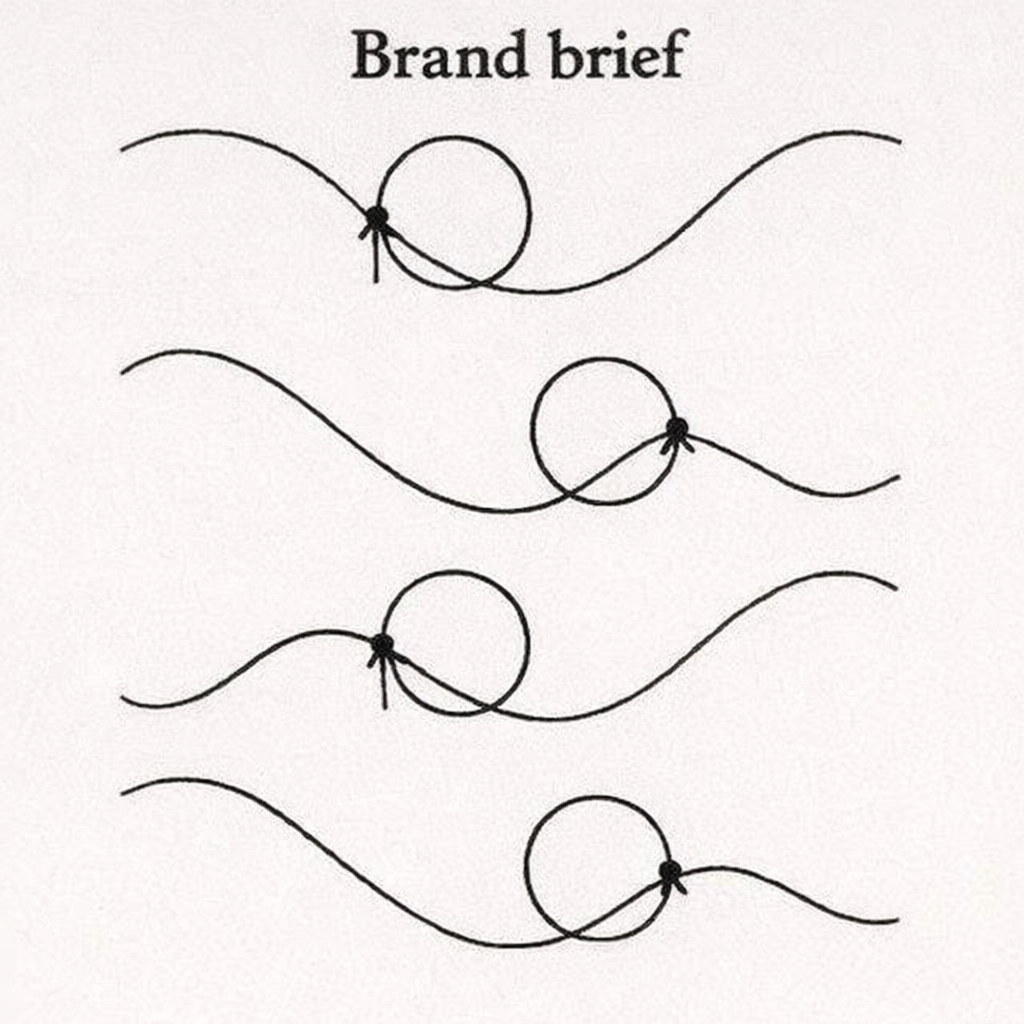

Too little direction produces unfocused exploration. The agency generates options across a wide range, hoping something sticks. This wastes time and money, and often leads to disappointment when none of the directions feel right—because “right” was never defined.

Too much direction stifles the value you’re paying for. If you’ve already decided the logo should be blue, use helvetica, and feature a swoosh, why hire an agency? Excessive prescription often means you’re outsourcing execution when you need strategic input.

The sweet spot is clear on outcomes, open on execution. Define what the brand needs to accomplish. Share relevant constraints. Provide examples of work you admire—and work you don’t—with explanation of why. Then let the agency do what you’re paying them to do.

Good agencies will push back if your brief is too prescriptive. They’ll ask what problem you’re solving, not just what solution you’ve already designed. If an agency accepts an overly prescriptive brief without question, they might be order-takers rather than strategic partners.

The one thing most briefs miss

Most briefs cover the what—what you need, what you do, what you want. Few briefs address the why now—what’s changing in your business that makes this the right moment for brand work.

This context matters enormously. A company rebranding because they’ve outgrown their startup identity needs different work than a company rebranding because they’ve acquired a competitor. A refresh driven by competitive pressure looks different than a refresh driven by channel expansion.

The timing and trigger for a brand project shape everything about how it should be approached. An agency that understands why you’re doing this now can calibrate their work accordingly. Without that context, they’re guessing at stakes and priorities.

Be explicit about the catalyst. What changed? What triggered this project? What happens if you don’t do it, or do it poorly? The answers focus the work and help the agency understand what kind of project this really is.

Setting up the relationship

A good brief launches the project well. But the relationship between client and agency determines whether the project stays on track.

Establish clear decision-making authority. Who can approve work? Who can provide feedback? Who has final say? Agencies suffer when they get conflicting input from multiple stakeholders, or when feedback from one person gets overruled by someone they’ve never talked to.

Define the feedback process. How will you review work? How much time do you need? How many rounds of revision are included? Clear process prevents misalignment and frustration on both sides.

Commit to honest feedback. Agencies would rather hear “this doesn’t work because…” than vague discomfort or enthusiastic approval followed by quiet disappointment. The best clients are specific about what’s working and what isn’t, even when it’s uncomfortable.

Be available. Brand projects require client input at key moments. Delays on your side cascade into delays on theirs. If you’re not able to engage when needed, the timeline and quality will suffer.

The bottom line

A great brief is an act of clarity and respect—clarity about what you need, respect for the agency’s expertise in figuring out how to deliver it.

The effort you put into briefing directly correlates with the quality of work you’ll receive. Agencies can’t read your mind. They can only respond to what you tell them. If you’re vague, you’ll get vague work. If you’re prescriptive, you’ll get order-taking. If you’re clear about outcomes and open about execution, you’ll get strategic partners working toward your actual goals.

The brief is the foundation. Build it well, and everything that follows has a chance to be great.